Research methods – why, how, why?

Posted: 13/02/2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: iterative design process, MDES06, Nesta, prototyping, research methods, systems innovation 1 CommentI presented my first go at an Action Plan to the group last week and although the clarity of the message on my slides possibly suffered from being put together pretty late last night, I felt by the end of the feedback and discussion with the rest of the group I had quite a good idea of what I am aiming at. After some persistent challenging from Sheila I realised that my plan to get more familiar with the subject of my research before narrowing in on a more focussed research question, which seemed like common sense when I wrote it down, was actually the product of exactly the kind of thinking that I have been trying to avoid. It is the antithesis of design thinking, of Agile development, of rapid prototyping, of any kind of iterative process. It’s waiting and waiting until the very end to produce something and then expecting that thing to be perfect. It assumes we’re dealing with complicated, but not complex systems (see Nesta’s report on Systems Innovation). Basically, it’s old school.

It was when I realised the importance of having not just a research question but also a hypothesis that everything fell into place. Like with prototyping, it doesn’t matter if the hypothesis is not right – in fact it’s probably better. Discovering that something is wrong gives you the opportunity to ask why and to learn more about what you’re trying to develop. This revelation then helped me to make sense of the research methods described in Real World Research by Colin Robson. It gives a basic outline of different research methods that can be used to study real world situations, including interviewing, observation and surveys. For each methods it describes subcategories as well as when these are appropriate, what activities they comprise, options for conducting them and advantages and disadvantages associated.

I’ve been really interested in these kinds of research techniques for some time, but never had an opportunity to use them. All the time I’ve wondered how it is that you can use observation and interviewing, which can come in various forms ranging widely in how structured they are, to produce evidence that is any more than a systematic kind of social value judgment. Once you have asked your questions and made all your notes on the various behaviours, then what? You can’t just take each sentence or action, or even pattern of actions, in turn and analyse all their various possible meanings in the hope of getting closer to some kind of insight or truth. But when I read Robson’s process of analytic induction, things started to fall into place:

This is yet another type of iterative development process! Pick a hypothesis, any hypothesis, and in doing so give your data something to fight against. Ask of that hypothesis, what does true look like? If the data looks different then keep refining and gathering more data until you the truth of the data matches the truth of the hypothesis.

MozFest #2 … learning journeys and personas

Posted: 12/11/2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: branding, design methods, learner journey, mozfest, personas, research methods Leave a commentThe Numiko stall caught my eye. Numiko are a digital agency working with Nesta to brand their digital making project. They were craftily using the event to do a bit of research for this project and I found the tools they used really interesting, especially because I can see that they could be of use in both of our current pieces of work at Ravensbourne.

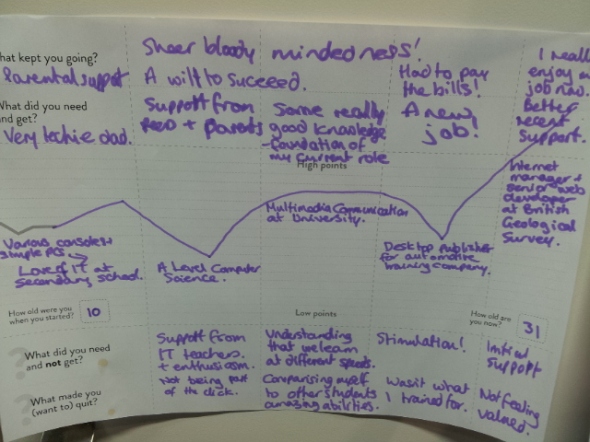

One method was creating learner journeys. MozFesters were invited to draw a graph of their own digital learning, where x was time and y was enjoyment. Here are a few pics I took of the results:

Another method was the creation of personas. The range of personas created contained some interesting insights, including that some learners are encouraged and engaged by having a peer cohort involved in a similar learning activity, or that to get excited by learning how to do something you first need to have a really strong idea of why you are learning it.

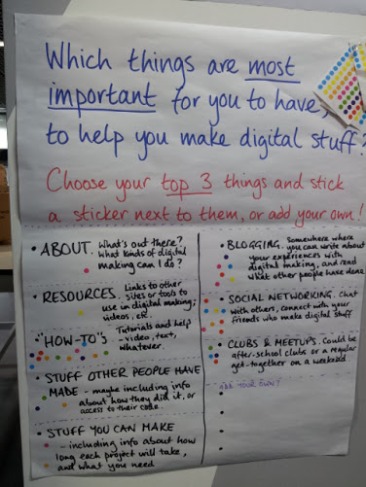

A method Numiko used to gain responses to different branding ideas asked participants to put dot stickers next words they liked and leave comments as to why:

I noted one contrast between these two research tools was the depth of engagement it required from the participant. The tool mused to gauge the effectiveness of a brand concept, something which is naturally done instinctively and instantaneously, was a very quick activity for the participant. The tool used to understand their long-term learning required much more thought, reflection and time. I think this distinction contributes to their effectiveness as tools and I shall try to remember this in my future research.

Let’s save the world

Posted: 04/10/2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: design methodology, research methods, sustainability 1 CommentWe started again on our sustainability project. We backtracked a long, long way along the road. We began again by simply post-iting anything and everything that came to our minds when we asked ourselves “what is it that we do that is bad for the world’s future?” Some of the results are above.

In an effort to bring some order to things we decided that our ideas could be roughly organised into four groups: Energy, Using Less, Waste Reduction and Macro/National change.

We weren’t exactly sure what to do next, so after a while we decided to brainstorm example of existing good practice in these areas. This is what we came up with:

ENERGY

|

REDUCING WASTE

|

USING LESS

|

MACRO/NATIONAL

|

The next idea we had was that it would be useful to analyse how each of these initiatives made a difference. We labelled each one by deciding whether it could be classed as Environmental (e.g. rainwater harvesting utilises environmental factors), Supply Chain (e.g. libraries encourage reuse), Behaviour Change (e.g. Meat Free Mondays), Efficiency (e.g. changing manufacturing processes to make waste less inherent) and Product Innovation (e.g. Paving slab energy transforms the energy of pedestrians’ feet into usable energy). We concluded that we would be best placed to pursue a solution based on behaviour change or supply chain design, as these do not require very specialist knowledge that we don’t have.

Rather than trying to create a solution from this exploration, we decided to do some more research focussing on two areas:

- Meat and animal processing

- Recycling at home

This research will involve seeking insights into consumer behaviour through observation and interaction, background research on existing infrastructure and targeting where inefficiencies and ineffectual processes lie.